"Okay, now lean back, tilt your head up. Cross one leg over the other-yeah, yeah." Directions from a husband to his posing wife-his much younger wife-on Charles Bridge in Prague. Stopping for every one of the 30 Baroque statues and statuaries that line the bridge on either side. Yes, the man must like his photogenic wife, but the fact that I watch them with an intent disgust for 30 minutes probably speaks to my tourist saturation. This is what the hot tourist spots always do. On one hand, you feel it necessary to see them, and on the other you dread the tourist onslaught and return to your hotel room feeling that you have just spent all day in a live museum. In Prague, the big tourist area is from Old Town, over Charles Bridge to Prague Castle. The buildings are beautiful, the scenery outstanding, the pedestrian traffic in July is a sucking eddy of despair, and so I find that I lose my present to a constant ranting inner voice.

I find myself confronting a common tourist conundrum: how to remind myself to be where I am, not to miss a thing? I have to admit that I failed on this particular day. The husband, the pretty wife-they robbed me of my resolve to fight the crowds. I was vaguely offended, but didn't quite know why. After all, I tried to tell myself, can't people see the world in whatever ways please them? Does this couple owe it to me not to perform an amateur Vogue photo shoot for the benefit of tourists like me who want to read placards and study history? My debate on proper tourist behavior forced me to walk over the bridge and arrive in a café just across the street from the famed National Theatre, where I sat with guidebook and materials I had picked up from the Castle Museum. I attempted to reclaim my enthusiasm, my desire to see the great landmarks, walk over Kafka's ghostly footprints. I hate to say it, but I failed at the café too, and soon found myself wandering aimlessly, thinking: I need a beer.

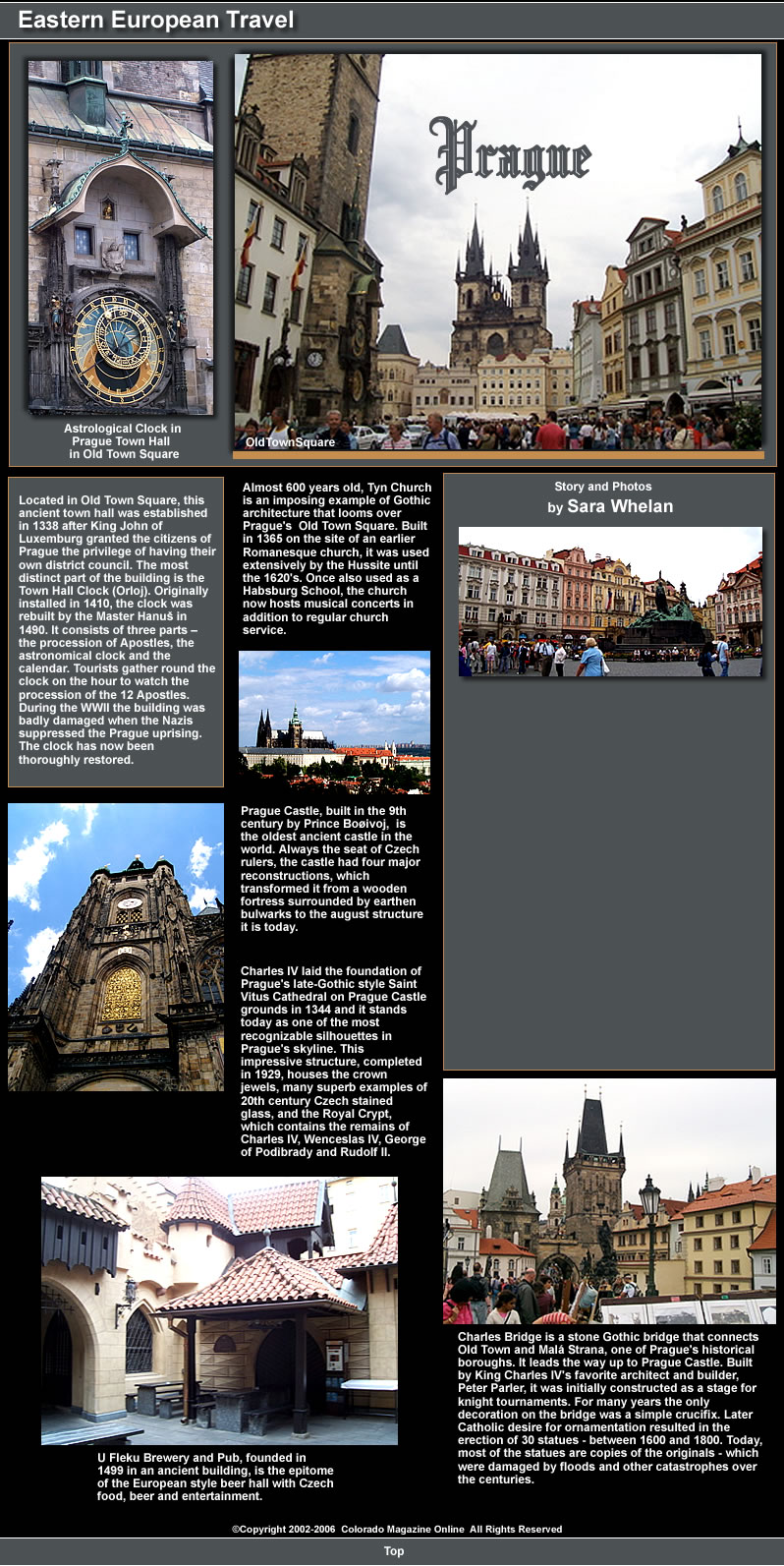

Now, it's not generally my policy to drink in unfamiliar places where I don't speak the language. But, Prague is well known for its beer and its beer gardens and my nifty little guidebook says there's one near by-U Fleku, which dates back to 1499. So, I wind my way through the streets, arrive at a modest building, its heavy wood doors facing the street, slip inside towards the sounds of an accordion played by a smiling white-bearded man. Bench seats line the walls, wooden tables stretch across the length of the small room. I am seated and immediately offered an aperitif, Becherovka, a unique Czech herbal drink. Soon another waiter sweeps down with a glass of dark beer. The guests at the beer hall break out into song and I feel like I'm having a Rick Steves moment, sans cameras. And soon the waiter swoops down, offering more aperitifs, and a second glass of beer. Yes, here they fill your glass until you beg them to stop or pass out cold. Wishing to avoid the latter, I quit after the second pint, exiting to the cool night air.

U

Fleku Beer

Garden

I intentionally avoid the Charles Bridge, back to my hotel by Kinsky Garden, a lovely and wild park in Prague. Though I had walked past the park several times, this evening I took notice of a simple abstract statue: a row of people apparently disintegrating against the forested backdrop. I go in for a closer look, find a placard that reads: The Memorial to the victims of communism is dedicated to all victims. Not only those who were jailed or executed but also those whose lives were ruined by totalitarian despotism. And though there's always the surface knowledge of history, here I find a personal realization of it. What's amazing about Prague, beyond the architecture, the great buildings, the romantic pedestrian walks, is its spirit, its resilience. There are not great statues commemorating the fall, or the rise of the new (but old) nation. There is more the sense of a simple and quiet reclamation of national identity: a beer that is 500 years old, a bridge that has stood against flood and war.

Memorial

in KinskyPark

As academic and perhaps idealistic as it sounds, I realized that culture wasn't a simple collection of monuments and statues, old buildings. What's emerging in Prague (and many cities in Eastern Europe) is a unique identity, something that had been muffled by 100 years of various regimes, and is now emerging as something-finally-self determined. This is exciting, really. This is something to discover, and so the next morning I ask the concierge how to discover it. He suggested a new museum.

Emergence

Just down river from Prague Castle is an old mill. An ordinary building from all sides, square, without many windows or decorations, and like most buildings in these old European cities, there's a book's worth of history sitting on its foundation. For a mill, the history is what one would expect: limekiln, barley-mill, draper's mill, burnt down, rebuilt, farmstead, artillery bulwark, flood, rebuilt, steam-mill. From as far back as the 10th century someone has dreamt up a purpose for the premises, and just a few years ago Meda Mladek dreamt it into a different purpose: a museum that featured eastern European artists who had suffered in silence behind the wall of the iron curtain.

"If a nation's culture survives, then so too does the nation," Jan, Meda's husband, was often quoted as saying. And for this pair of Czechoslovakian exiles preserving their artistic cultural heritage through the smothering communist years was not a hobby, but an ambition since they met in Paris in 1953. The couple spent a lifetime building the most extensive collection of this kind of art in the world to underscore that premise. And with the Kampa Museum, the Mladek's dream of turning over their private collection to their homeland is fulfilled. Unfortunately, Jan passed away before Czechoslovakia saw independence in 1989.

A retrospective on Kupka, considered an pioneer of abstract art, is one of the main features of the museums permanent collection, which also includes works by Otto Gutfreund, a Czech sculptor, and several more Czech, Slovak, Polish, Hungarian and Yugoslavian artists.

After leaving the museum, I took another walk across the famed bridge. It was still choked with tourists crowding statues for pictures. But this time, I also the easels-the artists who come here from all over the world to paint the Vltava river, the picturesque city grown up along its banks. I walked along Golden Row, a row of houses in the castle district where Charles's astronomers, numerologists and mathematicians are thought to have lived, and took a moment at Number 22, made famous by one of its occupants, Franz Kafka. Maybe this has always been a place of creativity, of life, of something almost ineffable.

Golden

Row

Franz

Kafka's

Former Residence

So, my best advice when you come to Prague is to walk across the Charles Bridge, from the castle to the Old Town Square. Remind yourself that Charles IV, for who the bridge is named, founded the first University and Prague, ushering in the city's first golden age in 1349. The great influx of intellectuals, artists, mathematicians, would make "Bohemian" a respectable term. Know that Charles personally laid the first stone on the Bridge on 9 July 1357 at 5:31 am, a strange and magical fact, a date and time chosen by staff of numerologists and astrologers who felt that this palindromic sequence of numbers (135797531 when one takes the year, the date and the time together) boded well for the bridge and the city of Prague. Enter the gaze of the stone faces of saints that line the bridge. And though you'll pass a line of religious figures and icons, (most of which were erected in the 1600s, long after Charles' time) realize that most of them are replicas, the originals often being lost to war or flood. But the bridge stands. And this somehow becomes the great metaphor for this city, the retention of its great Bohemian light with its enchanted divine numbers, under the face of religion, politics and war.

Travel

Tips

______________________

Phrase Books won't do the trick. Common phrase books are inadequate, especially in terms of pronunciation. If possible, study up with a tape before making your journey and familiarize yourself with the sound of the language.

Music is everywhere in Prague. However, no matter how charming the men in period dress peddling Mozart concerts are, try a concert at Rudolfinum, well known for its quality.

Visit a beer hall, but count your change! Check your bill. The waiters are also very charming, but if they suspect you may have had a few too many they might attempt to give themselves a hefty tip by stiffing you on change or inflating a few numbers.

Prague is a great city for walking. In high tourist season (which is almost year round anymore), tackle the more popular sites early in the morning or after dinner-especially the Charles Bridge, which offers great views and romantic landscapes.

Let hotel reception make reservations for you at a nice restaurant. Most of the finer eateries require reservations. Order some pork (local specialty), and-again-count your change.