Besides, what's with the spelling of its name? And how do you pronounce it?

Starting with the last questions, (wah-ha?-kah) is a name in the ancient Zapotec language spoken by many of the indíjenas (indigenous peoples) who comprise about 40% of the population in the Oaxacan state. And they encompass several different cultures-Zapotec is just one-with roots that go back at least a couple of thousand years before the Spaniards arrived in the New World.

Don't feel badly if this comes as news to you. The Mexican government barely recognizes these people. Most live in tiny villages, rather than towns, and are lucky to get much of anything in the way of resources-electricity, running water and paved roads. Most speak one of 16 ancient indigenous languages and only some are fluent in Spanish.

Their largest source of income is the money sent from the United States by their sons and daughters, siblings and cousins, who are working in our country- frequently without legal status.

And those who stay behind sell their fruits and vegetables as well as the beautiful handicrafts that Oaxacan natives have been producing for, well-nobody knows for sure how many tens of generations.

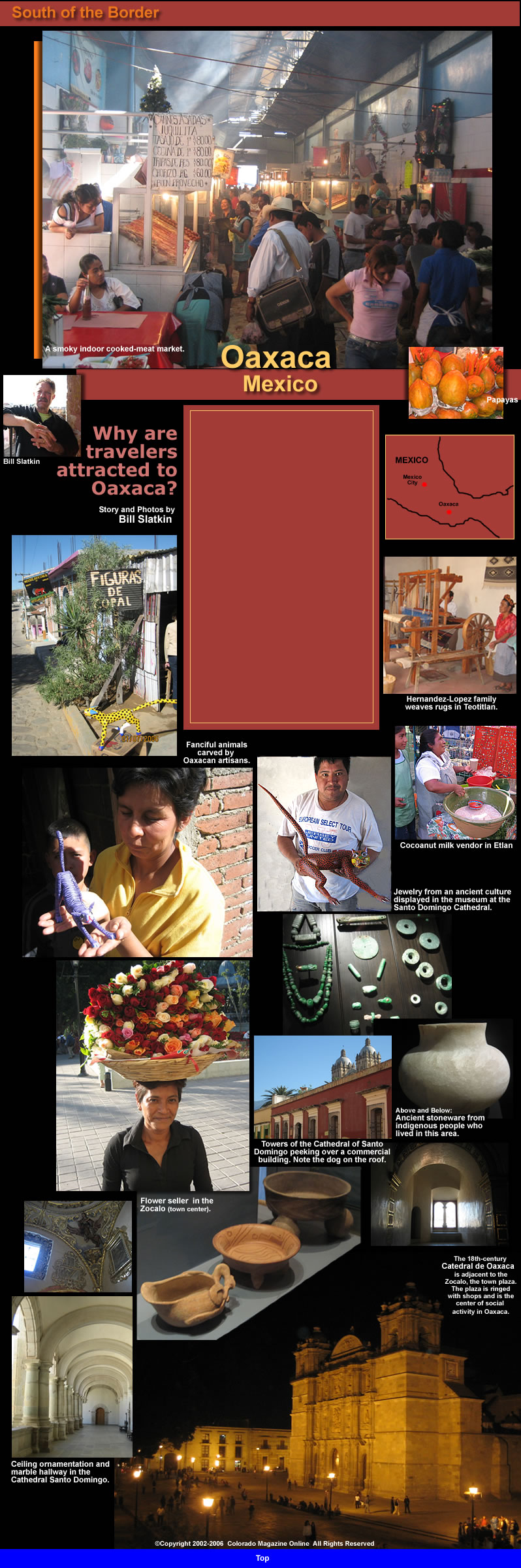

That's one of the secret's of the area's appeal, incidentally- the opportunity for those of us burned-out by the bigbox shopping experience, to purchase jewelry, fabrics, rugs, pottery, clothing, paintings and those wonderfully colorful wood sculptures of animal caricatures, directly from the people who created them. Often, with some bargaining over the very affordable prices.

The animal sculptures are probably the best known form of art from this region. Called alibrijes, which I'm told means "imagination of a Mexican," many are produced by artisan families who live in the village of Arrazola, a twenty-minute ride over rough roads from Ciudad Oaxaca.

Picture a dragon with blue and green spotted skin, bright yellow horns and a long, and curly striped tail. Or visualize a panther positioned in a threatening pose, but looking rather comical with its mixture of colors and its features reminiscent of tigers and house cats. You get the idea.

The alibrijes are carved from soft woods grown in forests near Arrazola, and are colored using dyes and pigments applied with cactus needles and other native painting implements.

I held my breath as I observed a boy, 10-year-old, at most, working with a razor-sharp knife on what would soon take the shape of a rattle snake. For a kid in my U.S. neighborhood, such an activity would probably result in a severed finger within minutes. But this youngster was already competent at the skills required in his family's artform/business, and the animal quickly emerged from the wood without a drop of the creator's blood.

For a few pesos, you can purchase a half-dollar-sized creature, such as a turtle or a chicken. My wife and I bought some geckos for good luck, at 100 pesos (under $10) each. And we got a dragon, a bit larger than our toaster, to ward off evil spirits, for 700 pesos. Others in our party were interested in still larger creations, including a magnificent peacock with its comb spread in a dazzling array of colors, for 1,200 pesos (a little over $100). That same piece might cost you two or three times as much at a gift store or gallery in a Mexican city, and even more, provided you can find it, in the United States.

In Etla, another village on the outskirts of Ciudad, Oaxaca (the main town of the Oaxacan state), we attended market day on miércoles (Wednesday), where dozens of natives congregate to sell foot-ball sized papayas, succulent golden pineapples, huge onions, carrots and other products of the land as beautiful as they are tasty. For five pesos I was permitted a swig of mezcal from a large plastic bottle that had been lipped by any number of other patrons, and smelled as if it had previously been used to transport diesel fuel. And someone handed me a Oaxacan delicacy, a small brown and crunchy chapolini (grasshopper for you uninformed Gringos) with an indescribable flavor that lingered on my palate long after I'd swallowed it. Another remaining part of the treat was a grasshopper leg which was wedged between my teeth for much of the afternoon, to the disgust of others in our party, who finally brought it to my attention.

(I'm the finicky restaurant patron, incidentally, who sends back a meal if I spy the faintest water spot on the any of the silverware).

Another shopping day found us in the beautiful village of Teotitlan del Valle where we watched the Hernandez - Lopez family produce gorgeous rugs with the skills and techniques passed down since the time of the Conquistadors. Maybe before then. This enterprise is what economists call a vertically-integrated business. They start with plants and insects, from which they develop their dyes. And they purchase sacks of recently-sheared wool which they spin into yarn. Using combs, looms and other implements of their craft, the six members of this family whom we met, create everything from small area rugs to rich looking room-sized floor coverings. Some are sold to dealers and wind up at stores in various cities in Mexico. But the best way to buy them is to pick out what you want from the selection laid out for tourists to admire at their rug-making facility in their home in Teotitlan.

But buying beautiful crafts directly from artisans is not the only reward for those willing to endure the extended travel (we changed planes twice on a journey that began in Los Angeles) to this remote area. As the home of several Mesoamerican civilizations, this region of the country is rich with wonders for the traveler who has a taste for history

The highlight for us in this regard was the thrill of walking the grounds at the crest of Monte Albán and viewing, from its cliffs, the vistas enjoyed by the Zapotecs, who constructed this mountain top city at least 500 BC, and by the succession of cultures that rebuilt and occupied Monte Albán's structures, over the many centuries that followed. Among the views we admired are the green valleys, some clusters of settlements on hillsides and, spread over the plateau to the east, la Ciudad Oaxaca.

View from Monte Albán

Zapotec Pyramid

We were short of breath as we roamed the site, exploring the plaza, the ancient playing field and the remnants of pyramids, homes and burial plots. Was that a result of the (5,200 ft) altitude, the dramatic views, or does it have to do with the spiritual feelings this place is said to inspire? Perhaps it was a combination of the three.

It wasn't until early in the Twentieth Century, by the way, that the Mexican Government began a serious effort at Monte Albán to collect and preserve the artifacts of the former civilizations - pieces of broken pottery strewn about the ground, and a wealth of ceramics, jewelry, even skeletons, excavated from burial vaults. What items had not been carted off by looters, are now housed in one museum on the Monte Albán site, and in a large and fascinating display that reveals much of the area's history - all the way up to the 1930s - at the Santa Domingo Church in Ciudad Oaxaca.

Though we spent a morning in this later location, trying to make sense of the stories about the area and of the country as a whole, there's just too much information to absorb in one session. And Ciudad Oaxaca plays an important role, not only as the site of many ancient peoples, but also as the birthplace or home of more modern figures, such as Porfirio Diaz, the dictator overthrown in the most recent (1910) of the Mexican Revolutions.

Our stay in Ciudad Oaxaca wasn't all about art and history, though. My wife and I spent most weekday mornings over a two-week period at la Academia Vinigulaza, an excellent and moderately priced language school that teaches English to residents, and exposes travelers to the words, phrases and even grammatical rules of el idioma Espanol.

Late afternoons often were dedicated to an important Mexican tradition - siesta. Back at our hotel, a 15-minute walk from the school, we took the chance to rest up from the day's activities and to marshal our energy so we could venture back out at sunset.

At the hub of Ciudad Oaxaca's central district is its town square, the zócalo, roughly the size of two football fields placed side by side, and laid out with benches, a bandstand, fountain and, because of the time of year, a large crèche illuminated at night with strings of lights arranged in the shape of a Christmas tree.

The zócalo is a popular gathering spot for residents as well as visitors. It's ringed on the east and west by several restaurants, all with outdoor seating.

We tried each of the places, frequenting a few that we particularly liked. Our routine was to carefully pick out a table that afforded a good view of the action, but was close enough to the restaurant building to benefit from its light. Yes, light. We needed to be able to see the notebooks in front of us, and the translation dictionary, so we could do our homework. That consisted of writing out a few phrases in Spanish, using words and sentence construction we'd learned that day,

Work

on our class assignments started once we got our drinks, usually dark beers,

sometimes shots of tequila, and a plate of cacahuates (salty Spanish peanuts

served with chunks of garlic cloves and red chilies). It would take an hour

or so to get around to ordering dinner, and in the meantime, we'd work a little

on our sentences and watch the fascinating show--the parade of Mexicans (indígena

and non-indígena) and visitors from near and far milling about the

zócalo. We were serenaded by marimba players, mariachi bands, individual

players and trios (with guitar, mandolin and recorder).

On December 30, a full symphonic orchestra showed up and played in a bandstand erected for the pre-New Year celebration. And one night a drum and bugle corps, from, I assume, the Mexican Army, marched in front of us, followed first by a color guard of uniformed high school girls, and then by locals who felt compelled to join the procession.

And of course there were the frequent visits to our table by those offering paintings, poetry, shirts and blouses, toys, fabrics, earrings, sweet treats and other food items I couldn't identify.

After two-and-a-half weeks in Oaxaca, enjoying its mild weather (daytime temperatures in the 70s, sometimes creeping into the 80s), its beauty, its friendly people, wonderful artwork and some interesting things to do and learn about, I had the answer to the question posed at the beginning of this article.