by Mel Fenson with Kelly Fenson-Hood

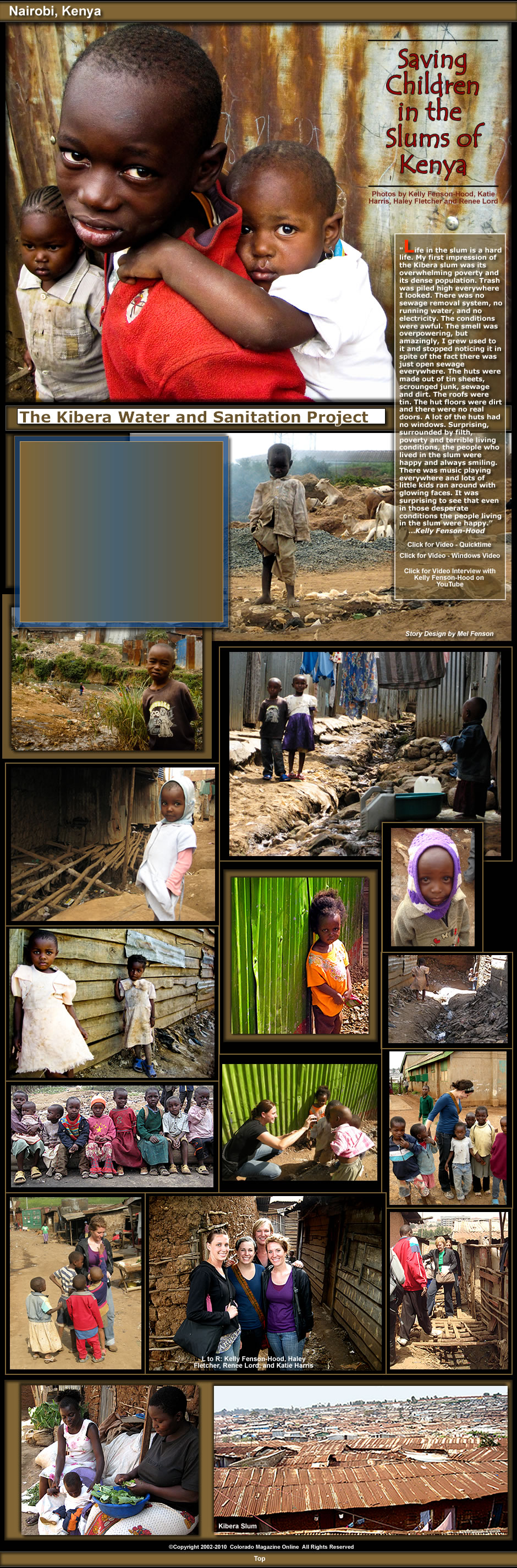

A University of Denver (DU) research team traveled to Nairobi, Kenya during the summer of 2009. Graduate students Kelly Fenson-Hood, Katie Harris, Haley Fletcher and Renee Lord spent three months conducting formative research in the Kibera slum, with assistance from their advisor, Renee Botta, PhD. Fenson-Hood described their experience there.

The research team interviewed fifty women in the slum to gather household-level data regarding awareness, practice and knowledge of contaminated drinking water and its connection to childhood diarrhea, which is one of the leading causes of death in children under age five in Africa. The research team sought to find out whether the interview respondents knew about and practiced water treatment methods, which could prevent diarrhea. Their research would provide the foundation needed to design a behavior-change campaign to educate women living in the slum about how to improve their family’s health by treating their drinking water.

The water contamination issue in the slum was a major health threat, according to Fenson-Hood. “Since there was no running water in the homes, the women had to collect it from from kiosks available in the slum - some were legal and others were illegal. The illegal ones were tapped into water lines from the city, which brought water into Kibera. Those taps, which were usually made of plastic pipes, laid on top of open sewage. Because they often had cracks and leaks in them, sewage seeped in and contaminated the water. People carried the water from taps back to their huts in 20-liter buckets.

Kibera, located within the city of Nairobi, is the largest urban slum in Africa, however, it is not recognized by the government as a formal settlement. It spreads over two-square miles and is home to approximately one million people - more than a quarter of Nairobi’s total population. Kibera has no running water, electricity, or sewage removal system - it is one of the most desperate and impoverished urban slums in the world. Half of its residents are under the age of 15.

There are nine villages within Kibera. The team focused their research in the village of Silanga. Fenson-Hood described the Kibera as a circle. “The more affluent people in the slum lived on the outer part the circle. The poorer people lived in the center of the circle. Silanga was in the very center of the circle and it had the worst conditions and the poorest people.” She further explained, “Some people do move toward the outside of the slum if they begin to earn more money, but interestingly, there are families who have the ability to move out of the slum, but choose to stay because it’s where their friends, families and community are.” The research team walked 30-minutes through the slum district to get to Silanga. “As we walked through the streets of the slum,” She observed, “we noticed that the conditions got worse and worse the farther we went - with more and more trash piled high.”

The

DU research project was conducted in conjunction with the Kibera Community

Water and Sanitation Project, sponsored by the Denver Southeast Rotary Club

and the Rotary Club of Langata in Nairobi. It was funded by a $300,000 3-H

Rotary International grant. This project constructed facilities to provide

water, flushing toilets and showers for slum residents. The DU project serves

to complement the facilities through a health education program. The initial

3-year grant was completed in September 2009.

Two local companies in Nairobi supported the DU research project - EcoTact,

a social enterprise company associated with the Nairobi Rotary Club, and Practical

Action, a non-profit organization, which implemented the Kibera Community

Water and Sanitation Project. Practical Action employee, Sadique Bilal, who

was also a Kibera resident, became the team’s main connection with people

in the Silanga village. He arranged all the interviews for them, met them

at the entrance to the slum, and walked them to the village, “which

is not a very safe place - especially for young, white women,” Fenson-Hood

commented. She added, “You really don’t want to be there unaccompanied

by a local. Sadique really took care of us while we were there - he was great!”

During their time in Kibera, the research team learned about its culture. Fenson-Hood noted, "Kibera’s family structure was typically comprised of a wife, a husband, and three to six children. The lifestyle was traditional. The husbands left the slum in the morning to work in the city, while the wives carried out traditional roles of taking care of the kids, preparing the meals, and attending to household chores."

“Most of the women did not have jobs, but we noticed a few tailoring businesses, and a some women roasted nuts to sell, while a few other women braided and styled hair. I saw one woman making jewelry, but because slum residents live in such extreme poverty, making under a dollar a day to support an entire family of maybe six, the ability to buy craft materials is nearly non-existent. They can hardly afford to buy coal to cook with,” Fenson-Hood remarked.

“People in the slum had a very strong sense of community and everyone there knew each other. The women would sit together and clean and braid each other’s hair and chat while the kids played. Actually, the kids were quite independent and had the ability to run around and do what they wanted, but the older children always looked out for the younger children. The kids always had smiles on their faces and I never ever saw any of them cry. They just kept themselves busy and played games and they made toys out of whatever they could find, such as a piece of string or other scraps they came across. They had nothing, yet they were happy,” Fenson-Hood observed.

“The kids did not shower every day,” Fenson-Hood continued, “they were always dirty and wore dirty clothes. A lot of the kid’s clothes were passed down and you saw kids wearing clothes that were too big for them, but they wore what they had. When the kids became of age and got into school, they did get uniforms. I noticed a lot of older kids wearing school uniforms.”

"Because Kibera is an informal settlement," Fenson-Hood explained, "and not recognized by the government, there is not a formal school system, but there are a lot of informal primary schools, which are equivalent to American elementary schools, and provide classes to 7th or 8th grade levels. Children are able learn the basics, but have few school supplies. The kids that make it all the way through primary school learn to speak some English, but most people in the slum speak only their native language, Swahali."

Fenson-Hood summed up her experience working in the slums of Kenya, saying, “I learned that development work is not an easy field, that there are many obstacles to overcome when working in a developing country, and to expect this type of project to be a constant uphill battle. However, there is a great need for this work to be done in order to improve the health of children in developing countries, and obstacles can be overcome.”

“There are a lot of ways to improve the lives of these children," She added. “So many children in developing countries die before the age of five, and these poor children are dying from preventable causes like dehydration from diarrhea. It’s just a lack of knowledge, information and practices that allow these deaths to happen. If the mother’s can be taught to purify the drinking water, their children's lives will be saved.”

"Regarding our future plans," Fenson-Hood said, “we are seeking additional funding to continue this project.” She added, “I plan to do my Master’s Thesis on this research and create the behavior change campaign to promote the treatment of drinking water in Silanga and I hope to go back to Kenya next summer to implement the campaign.”

Kelly Fenson-Hood is a graduate student at the University of Denver, working toward a Masters Degree in Health Communication and Social Marketing with the hopes of working on children’s health development after graduation.