Edward

Hopper was a

prominent

20th Century American realist painter. His compelling, stark, moody style

removes viewers from the present and takes them away to an earlier time and

place in American history. His work reflects the heartbeat of both urban and

rural American life with scenes of people, architecture and landscapes - rendered

in both oil and watercolor. His popularity continues to grow even today.

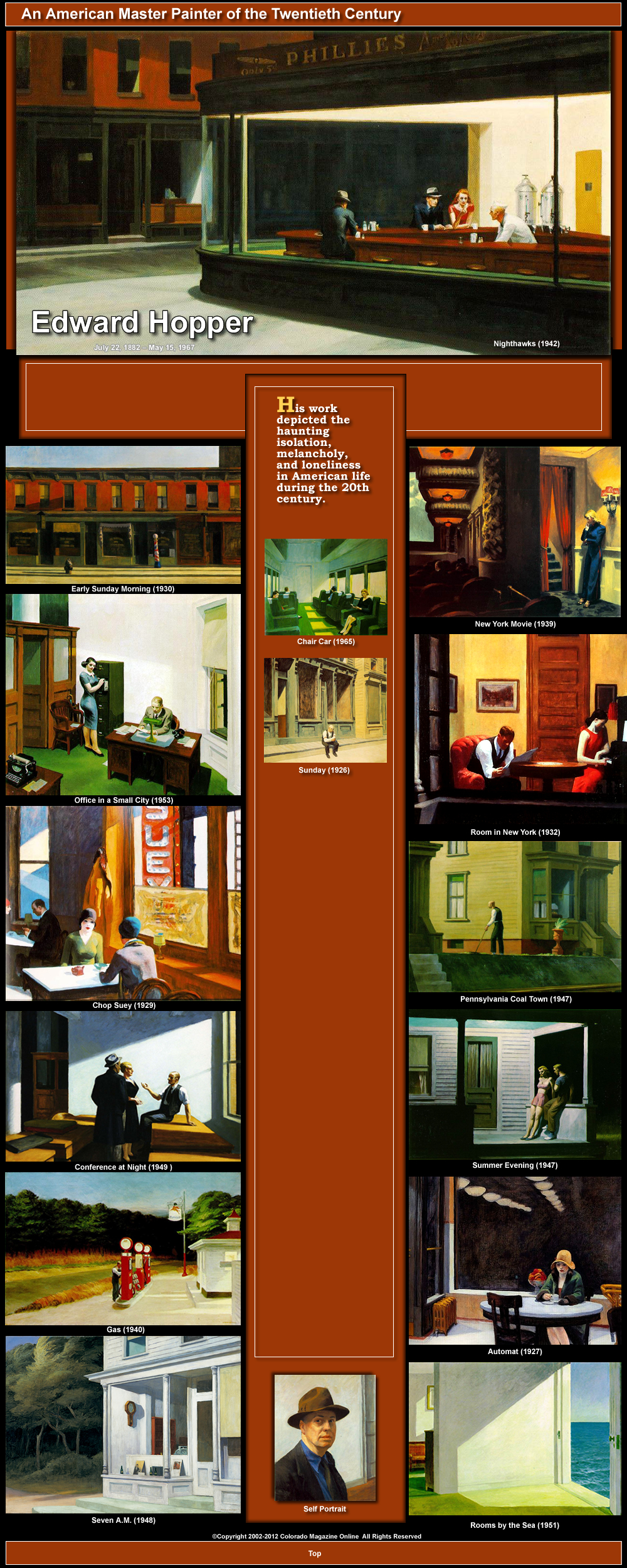

Hopper drew inspiration for his subject matter from the every day ordinary aspects of American life. His primary emotional themes were solitude, loneliness, regret, boredom, and resignation. He painted removed people placed in settings, such as desolate gas stations, sleezy motels, barren rooms, nighttime cafes and movie theaters. His subject matter included cityscapes that captured the pulse of metropolitan life with street scenes populated by people doing what ordinary people do in their daily lives. Hopper reduced his city images to sparce geometric impressions that portrayed desolation and danger, rather than elegance or pleasure. His seascapes and rural landscapes were simple but intriguing.

The best known of Hopper's paintings, Nighthawks (1942) pictures a few cheerless customers sitting silently at the counter of an all-night diner. The perspective is from outside the diner. The harsh electric light sets a cold, discordant mood. As in many Hopper paintings, the interaction of the people is minimal.

In his, Summer Evening, a young couple talking in the harsh light of a cottage porch, is inescapably romantic. “The figures were not what interested me,” Hopper noted, “it was the light streaming down, and the night all around,” that created the effect he wanted.

Hopper approaches Surrealism in, Rooms by the Sea (1951), where an open door leads to an expanse of water - without a ladder or steps. What did this curious setting mean?

In Hopper’s, Room in New York (1932), a young couple appears alienated and uncommunicative. He reads a newspaper, while she idles by the piano. Where was their relationship headed?

In, Office at Night (1940), Hopper creates a psychological puzzle. The painting shows a man focusing on his work, while nearby, his attractive female secretary pulls a file. The scene is steamy with sexual innuendo and tension and leaves the viewer wondering if the man is either truly uninterested in the woman's appeal or whether he is trying to ignore her.

Hopper was a slow and methodical artist. He wrote, “It takes a long time for an idea to strike. Then I have to think about it for a long time. I don’t start painting until I have it all worked out in my mind. I’m all right when I get to the easel". He often made preparatory sketches to work out his carefully calculated compositions. For New York Movie (1939), Hopper did more than 53 sketches of the theater interior and the figure of the pensive usherette.

Hopper emphasized the use of bright sunlight and shadows to set the moods in his paintings, such as, Early Sunday Morning (1930), Summertime (1943), Seven A.M. (1948), and Sun in an Empty Room (1963).

Once Hopper attained his mature style, his art remained consistent and self-contained in spite of the numerous art trends that came and went during his long career.

Hopper was born in upper Nyack, New York to middle-class parents of Dutch decent.

His’s artistic talent was evident by the time he was five years old. His parents encouraged his art and kept him supplied with art materials and reference books. By the time he was a teenager, he was working in pen-and-ink, charcoal, watercolor, and oil media. In 1895, he produced his first signed oil painting, Rowboat in Rocky Cove, which revealed his early interest in nautical subjects.

Hopper studied art at the New York Institute of Art and Design. One of his instructors, Robert Henri, advised his students that, “It isn’t the subject that counts, but how you feel about it.” He said to, “Forget about art and paint pictures of what interests you in life.”

Early in his career, Hopper worked in an advertising agency as an illustrator, designing covers for trade magazines. Although he did not like illustration, the need to earn a living kept him there until the mid-1920s.

Living in New York, during the early 1900s, Hopper struggled to define his own style. During this time, his painting languished and he commented, “it’s hard for me to decide what I want to paint. Sometimes I go for months without finding it. It comes slowly.”

In 1913, at the famous Armory Show, Hopper sold his first painting, Sailing (1911). He was thirty-one at that time, and although he hoped his first sale would lead to others in short order, his career did not take off for many more years to come.

In 1913, Hopper moved to an apartment in Greenwich Village in New York City, where he lived and worked for the rest of his life.

In 1920 and again in1922, Hopper had a one-man exhibitions at the Whitney Studio Club, which were precursors to his permanent exhibit at the Whitney Museum.

Two of his notable oil paintings in the 1920s were, New York Interior (1921) and, New York Restaurant (1922). He also painted two of his many “window” paintings which show female figures - some clothed and some nude - gazing out of apartment windows, acquiescing to life.

During a summer painting trip to Gloucester, Massachusetts, Hopper saw Josephine Nivison, whom he had met at art school. They married a year later and she assumed the management of his career and became his primary model and life companion.

By 1924, at the age of forty-one, Hopper had finally received the recognition he deserved. With his financial stability secured, he continued to live a simple, stable life, and continued to create his distinctive styled paintings for four more decades.

His stature took a sharp rise in 1931 when major museums, including the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, paid thousands of dollars for his works. He sold 30 paintings that year, including 13 watercolors. The following year he participated in the first Whitney Annual, and he continued to exhibit in every annual at the museum for the rest of his life. In 1933, the Museum of Modern Art gave Hopper his first large-scale retrospective.

Hopper’s final oil painting, Two Comedians (1966), painted one year before his death, focuses on his love of the theater. Two French pantomime actors, one male and one female, both dressed in bright white costumes, take their bow in front of a darkened stage. Jo Hopper confirmed that her husband intended the figures to suggest their taking their life's last bows together as husband and wife.

Hopper died in his studio near Washington Square in New York City on May 15, 1967. His wife, who died 10 months later, bequeathed their joint collection of over three thousand works to the Whitney Museum of American Art. Other significant paintings by Hopper are held by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, The Des Moines Art Center, and the Art Institute of Chicago.

Hopper’s birthplace and boyhood home was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2000. Today the house is the Edward Hopper House Art Center.

Edward

Hopper’s popularity has continued to grow through the years with exhibitions

of his work displayed in major museums in the US and Europe.

Edited by Mel Fenson from material gathered from the web and other sources.

|

|