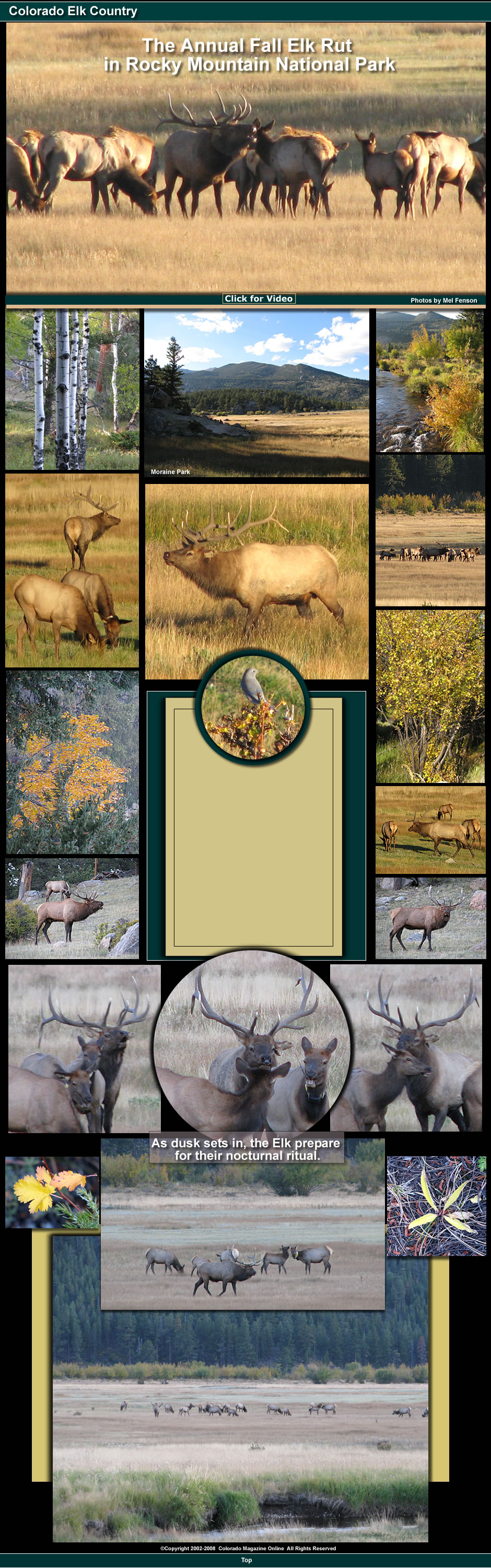

Gathering herds of elk may be seen along the edges of clearings early in the morning and in the late afternoon and evening. During this annual season, bull elk compete with one another for the right to breed with a herd of females. The larger antlered males, which can weigh up to 1,100 pounds and stand five feet high at the shoulder, move nervously among the bands of smaller females, fending off intruders and herding back strays, who wander off. Prime bulls, eight-to-nine years old, stand the best chance of mating. Although competition is high among bulls, little fighting takes place because fighting causes injury and depletes energy. Instead, mature bulls compete for cows by displaying their antlers, necks and bodies. They emit strong, musky odors and bugle. With little rest or food during the mating season, bulls enter the winter highly susceptible to the hardships of the coming months.

Cow elk, weighing up to 600 pounds carry their new life for 250 days through the rigors of winter and early spring. In late May or June, they give birth to lightly spotted calfs, which weigh about 30 pounds. Nursing and foraging through the rich seasons of summer and fall, the calves may reach 250 pounds by late autumn.

According to the National Park Service, North American elk were once plentiful in the Rocky Mountain National Park area but as Euro- Americans settled the Estes Valley and hunted elk, few remained by 1890. In 1913 and 1914, before the establishment of the park, the Estes Valley Improvement Association and United States Forest Service transplanted 49 elk from Yellowstone National Park to the area. An effort was also mounted to eliminate predators, including the gray wolf and the grizzly bear. As the number of predators decreased, the elk population grew. A problem exists today, however, as acelerating development along the park boundary is diminishing the amount of open space, blocking traditional elk migration routes, and decreasing winter forage and habitat.

Edited

by Mel Fenson from

National Park Service information.

|

|